NC House lawmakers propose ‘long overdue’ reforms to child welfare system

By Grace Vitaglione

Gaile Osborne is a foster parent to six children. She would’ve had seven if her first foster child had been allowed to stay with her, she said.

Instead, her county Department of Social Services decided to put the 4-year-old back with her biological mother in what Osborne thought was a premature decision. She and her husband spoke up, she said, but were labeled as “overstepping boundaries.”

Later, she learned the child had subsequently been placed back into the foster care system repeatedly, but no one had reached out to Osborne to ask if she would take her in.

“As a mom sitting here with an open home, a license and open beds — to find out that she’s been all over the place — it just breaks your heart,” she said. Osborne later became an advocate for foster children and is now executive director of Foster Family Alliance of North Carolina.

New legislation in the North Carolina House of Representatives, filed March 31, could prevent such situations from happening again, Osborne said. Among other changes to the child welfare system, House Bill 612 would allow a judge in a local court to review a county’s social services proposal to remove a child who had been with a caretaker for the preceding year under certain conditions.

If this bill had been in effect back then, Osborne could have appealed to a judge or the state Social Services agency for custody of the little girl.

The legislation, sponsored by Democrats and Republicans in the House of Representatives, aims to improve North Carolina’s child welfare system — in part through increased state oversight of county departments of social services. The bill is also intended to facilitate finding placements more quickly for foster youth with behavioral health needs.

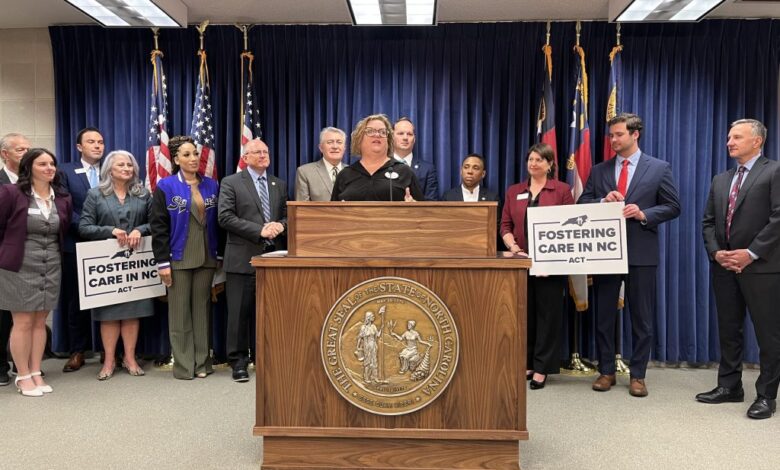

The changes are “long overdue,” said bill cosponsor Rep. Allen Chesser (R-Middlesex) during a news conference at the legislature on April 2.

This bill is part of a continuum of necessary reforms, said Karen McLeod, who runs Benchmarks, an umbrella nonprofit organization that advocates for groups that provide care for children and families.

History of challenges

There have been successive stepwise efforts to reform the child welfare system over the past decade, and they gained momentum after several high-profile failures. One of those was the 2016 death of 23-month-old Rylan Ott, a Moore County boy whose death inspired an eponymous law intended to overhaul the child welfare system.

A key reform that sprang from Rylan’s Law allowed the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services to create regional offices to provide training and guidance to counties. Lawmakers also gave the state health secretary the ability to take over a county department of social services if it becomes clear the county can’t or won’t make things better, as happened in 2018 in Cherokee County and Bertie County in 2022.

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services has also worked on fixing these problems through changes like a statewide Medicaid plan to cover foster children and rolling out software to track children in the system.

But other reform efforts have struggled to make headway in the General Assembly. In the 2023-24 legislative session, Senate Bill 625 would have given the state more authority in child welfare cases. That bill eventually failed after members of the House of Representatives weakened the state’s authority in the bill’s language.

Legislative watchers explain that House lawmakers, because they represent smaller constituencies, can sometimes be under greater pressure from county boards of commissioners and social service directors who resist a loss of local control.

This year is likely to be different. The new bill is starting out in the House, where it has broad support, with more than half of the 120 members signing on as co-sponsors.

Chesser said the Senate is waiting for House passage of the bill, which is set to be heard in the House Judiciary 1 committee on April 15.

Strengthening state oversight

One of the primary challenges in North Carolina is that the state health department manages — and has ultimate accountability — for the child welfare system, but that department doesn’t actually run it day to day.

That work is left up to North Carolina’s 100 counties, where the quality of the work and the resources available to county workers can vary widely.

Calvisha Wilson of Forsyth County was once in foster care. She’s an alumna of Strong Able Youth Speaking Out, or SaySo NC, a statewide association of people ages 14 to 26 who are or have been in the substitute care system in North Carolina.

She said it would help to have more consistency statewide because that would bring more accountability to the system.

“Foster care is never easy to walk through,” she said.

House Bill 612 would allow the state Division of Social Services to review cases and intervene if needed, McLeod said. It would also require a county to hand over a case to another county or to the state if there were a conflict of interest within the department — something that’s been a problem in the past.

Too few foster parents

Recruiting foster parents has always been a challenge, but those challenges grew during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, when the number of willing parents diminished while the number of children needing foster care remained steadily high, said Rep. Donnie Loftis (R-Gastonia) at the news conference.

There were just under 11,000 children in foster care in NC as of January 2025, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Jordan Institute for Families.

Allowing more state oversight will indirectly help with foster parent recruitment and retention, Osborne said. Currently, she said, foster parents who make a misstep can face retaliation from a county department of social services. Sometimes that means removing a child from their foster parent.

“Our kids lose because they lose homes that they’ve been in for years … and we’re going to lose that parent who is a good foster parent,” Osborne said. “We don’t have space to lose people.”

Jerrie Teague has been a foster parent for almost 11 years and, in total, has fostered 51 kids, in addition to adopting four. She runs a regional support group for foster families and said she’s heard multiple stories of people asking for help when children are removed without notice.

But in the past, state staff said their hands were tied, Teague said.

For example, a parent may advocate for their foster child to receive an Individualized Education Plan in school, but Teague said that if a county social services worker doesn’t want to pursue that, the parent may be told they’re overstepping their bounds.

“People treat us like glorified babysitters: ‘Take care of them, treat them like your own — but you don’t have a right to say what they need,’” she said.

follow our coverage of state health policy

Finding places for kids with behavioral health needs

The plunging number of foster homes in North Carolina has also created a crisis for many children who need an emergency place to stay. This has led to children across the state being forced to sleep in county social services offices, hotel rooms and converted storage closets.

That’s in part because more foster children — like other kids across the board — have mental or behavioral health issues in the wake of the pandemic that make them hard to place. These kids can end up spending weeks in inappropriate settings, like hospital emergency departments, while they wait for a place to stay.

House Bill 612 would create a Rapid Response Team within the state health department to find appropriate placements for these youth faster and would limit hospitals’ ability to discharge a child without an appropriate place to go.

When a foster care child ends up in a hospital in need of mental health treatment, the bill would also require their insurer to initiate an assessment for them within 72 hours of notification. Before, they had five business days to initiate those assessments.

Reducing punishment

House Bill 612 would also allow for open adoptions, where the biological parents of a child and the prospective adoptive parents agree to have some form of contact after the adoption.

This would facilitate the adoption process, according to the Foster Family Alliance of NC, because parents would be more willing to relinquish parental rights if they had assurance they would have some form of relationship with the child later on.

The bill would also prevent a county department of social services from terminating a parent’s rights for failing to pay child support. Many of these parents lack the resources to pay.

Marcella Middleton, who went through foster care in N.C., said that’s important because penalizing the parent also hurts the child.

“Kids don’t think about the financials, they think about the bond and their connection with their family,” she said.

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST

The post NC House lawmakers propose ‘long overdue’ reforms to child welfare system appeared first on North Carolina Health News.