What’s it like to return home from incarceration? Hands-on simulation highlights some of the challenges of reentry

By Rachel Crumpler

Ninety-five percent of incarcerated people in North Carolina will eventually be released back into the community — roughly 18,000 people return home each year from state prisons and thousands more from county jails.

It’s a day that people yearn for, but also a day met with trepidation and fear.

“When you first go in, especially if you’ve never been to prison before, that’s the most stressful time,” said Scott Brooks Jr., who spent nearly 23 years in federal prison. “The second most stressful time is the last six months before you get out.”

For many people, walking out of the doors of a prison or jail marks the start of new hardships and challenges as they work to rebuild their lives in the community. Challenges related to navigating life with a criminal record abound, from securing employment to finding a safe place to live — and people often don’t have the means or support to do so successfully.

An April report released by the North Carolina Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission found that from a sample of 12,889 people released from North Carolina state prisons in fiscal year 2021, 33 percent were sent back to prison within two years of their release.

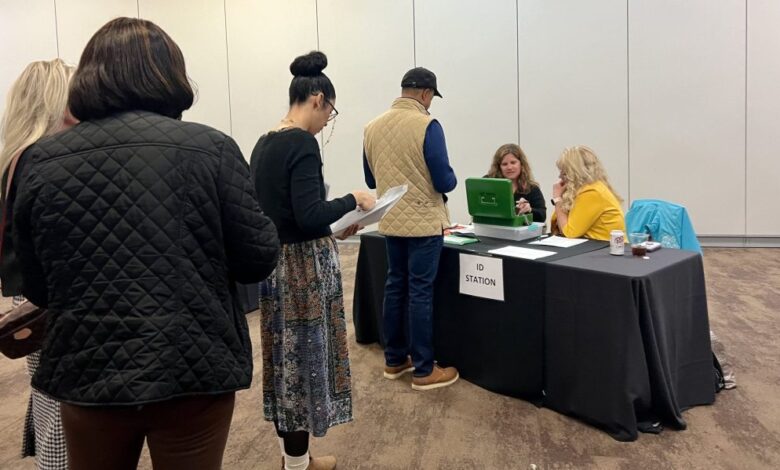

For an hour last week, about 40 community members — including me — experienced some of the challenges formerly incarcerated people encounter by participating in a reentry simulation.

Trillium Health Resources, a local behavioral health management organization serving residents in 46 North Carolina counties, hosted the exercise last week as part of the i2i – Center for Integrative Health conference in Winston-Salem to illustrate and deepen participants’ understanding of the barriers faced by people as they transition from incarceration to the community.

Donna Salgado, a formerly incarcerated woman who serves as a peer support specialist and community health worker on Trillium’s reentry team, said expanding the community’s understanding is vital to building a society with better support. After all, she said, the community is where formerly incarcerated people come back to, and it’s the community’s mindset that has to change.

“You can’t do better until you know better,” she said.

Exhausting reentry experience

The simulation, structured in four 15-minute increments, represents one month in the life of someone recently released from incarceration. Organizers handed out packets to each participant with our temporary identities and a list of tasks that needed to be completed each week.

For the hour, I walked in the shoes of someone returning to the community after serving 10 years in federal prison for robbery and possession of a firearm as a felon. I also had a history of substance use disorder — a condition that affects about 60 percent of incarcerated people.

I left prison with a GED and no money.

Organizers gave little instruction about where to start our reentry journey, and the list of to-do tasks felt daunting, particularly given my lack of resources and support.

We moved around the room visiting stations representing various locations, such as probation, employment, court, medical care, food bank, pawn shop and church — trying our best to complete our mandatory tasks. However, barriers like inadequate transportation, unhelpful workers or stations being closed for a lunch break often derailed progress.

I worked a part-time job that didn’t pay enough to cover my rent or my child support payments. Over the four weeks, I managed to keep myself fed, but that’s about it.

I tested positive for drug use on three out of four of my urine tests, which led my probation officer to send me to court where I barely avoided reincarceration. Treatment was difficult to access, as I tried to visit the station where I could receive help twice when they were closed. I sought to earn extra money to pay for the treatment by donating plasma, but I was told I was anemic and unable to donate.

Failing to complete my assigned tasks was frustrating and defeating; it was a shared feeling around the room. Several participants simply sat down early because they didn’t know what to do or didn’t have the resources to move forward.

Luz Terry, Trillium’s vice president of enterprise-wide training and staff development who led the simulation, interjected when she saw this, reminding us that sitting down isn’t an option in real life — not when trying to land and stay on one’s feet after incarceration.

But the exasperation from facing obstacles was palpable. One participant I crossed paths with said, “I just need to go to jail. This is too hard.”

Peer support key to success

By the end of the simulation, only two out of the dozens of participants managed to complete all their required tasks.

I was not one of them.

The two successful participants were paired with a peer support specialist — people with lived experience of incarceration.

Stephanie Payne, a participant provided with peer support, said the guidance made all the difference in navigating the reentry process.

“I definitely wouldn’t have finished an entire week without the peer support,” Payne said. “I didn’t know what I was doing. I felt highly supported by the peer. He knew what he was doing, and I could trust that he was going to help me get what I needed to get done.”

Brooks, interim coordinator of Trillium’s reentry program and a certified peer support specialist, said more money needs to be allocated to expand peer support across the state. He said it’s a powerful investment because peers foster credibility and inspiration that can result in better outcomes.

“Success breeds success,” Brooks said. “When a person is inspired by somebody that’s been there, it makes them believe that they can do it too. And I think that helps not just with the [formerly incarcerated] people we’re working with but some of the officials we’re working with.”

Payne said the reentry simulation was eye-opening. She works as an admissions and outreach counselor at Project Transition in Wilmington — a program serving people with serious mental illnesses and substance use disorders facing homelessness, including those who have been previously incarcerated.

As a result of her work, Payne said she was already familiar with some of the reentry challenges faced, such as obtaining driver’s licenses, filling out housing applications and scheduling health care appointments. However, she said the simulation opened her eyes even wider.

“It’s wild how we expect people to hop out of a jail or a prison or the hospital and just kind of say, ‘OK, good luck,’” Payne said.

State focused on improving reentry support

This year, state leaders have been working to improve support for people leaving incarceration to make the transition smoother and more successful. They realize that’s critical since the vast majority of the state’s incarcerated population will one day return home.

Gov. Roy Cooper’s Executive Order No. 303 kicked off North Carolina’s concerted effort to bolster support for this population. The January directive called for a “whole-of-government” approach to boosting reentry services for formerly incarcerated people across the state and enrolled North Carolina in Reentry 2030 — a national initiative aimed at dramatically improving reentry success.

The Joint Reentry Council, created by Cooper’s executive order, immediately went to work developing a strategic plan to tackle some common and pressing problems people face when leaving prison, particularly access to health care, economic mobility and housing opportunities.

This month, the Joint Reentry Council released its first progress report showing steps taken thus far to strengthen reentry support. Of the 133 strategies outlined in the Reentry 2030 Strategic Plan released in August, 50 are already in progress or completed.

Some of the accomplishments include:

- The Department of Adult Correction began submitting Medicaid applications for incarcerated people nearing release.

- DAC and the Division of Motor Vehicles partnered to provide state identification cards.

- DAC designated seven more prisons as reentry facilities, where programs and services are offered to incarcerated people nearing their release to prepare for the transition. One of those is a close-custody prison, the highest security level, which increased the total number of facilities designated for reentry to 21.

- The establishment of more Local Reentry Councils that act as hubs to resources in the community for formerly incarcerated people.

- Joint Reentry Council member Kerwin Pittman founded the Recidivism Reduction Call Center, a hotline designed to help connect formerly incarcerated callers to jobs, housing and other services to help them succeed as they exit incarceration.

“The Reentry 2030 Initiative is both the right thing and the smart thing to do for our state,” Cooper said in a news release about the progress report. “It’s the right thing to give people opportunities to be ready for release from prison with strategies to take care of themselves and their responsibilities along with the training to get a job. It’s also the smart thing to reduce repeat offenders and keep the public safe.”

Call to action

Cindy Ehlers, chief operating officer at Trillium, ended the reentry simulation with a call to action for participants.

“The challenge here is to take what you learned today and really go back to your community and see how you can impact change,” she said.

Several Trillium team members attending a reentry simulation in Carteret County in May 2023 is what “set a fire” for the organization to do more for this population, Ehlers said.

Trillium launched a reentry program called T-STAR — Trillium Support Transition and Reentry — in 2023 serving adults released from prison who have serious behavioral health conditions. They’ve also reviewed internal hiring procedures, hosted reentry simulations attended by about 600 participants and are working to build transitional housing for formerly incarcerated people. And they’re still looking at what else they can do.

“One of the things that I took away from the first time and every time I participate in this is ‘Trillium has still not done enough,’” Ehlers said.

Trillium’s efforts along with those of state agencies, nonprofits, housing partners, community colleges and community members across the state will be important in meeting North Carolina’s Reentry 2030 goals of lessening obstacles that could derail someone’s transition back to the community.

Brooks emphasized that reentry support is not giving someone leniency, it’s about providing people the second chance they deserve.

“The vast majority of people going into custody are going to get out; they don’t have life sentences,” he said. “We’re just trying to keep society safe by helping these people have a fighting chance.”

The post What’s it like to return home from incarceration? Hands-on simulation highlights some of the challenges of reentry appeared first on North Carolina Health News.